Being a little impatient I found myself slightly annoyed on the London Underground this week by a closed station. It wasn't that the station in question was my stop, it was simply that the train went on a go-slow when it approached and went past the station to maintain the schedule for the train but without actually stopping. Overall the journey time wasn't changed, but this didn't stop the slightly irrational feeling that I was being held up.

Whether it's a traffic jam, the delay of a plane or crowded streets, no one seems to like a loss of momentum.

Interestingly, momentum and the need to maintain it is one of the main aims for Controlled Motorways which use techniques like Variable Speed Limits. The thinking is that as roads near capacity due to congestion, it's possible to increase capacity by controlling driver behaviour - making it more uniform. When people are advised with the messages "Congestion - Stay in Lane" and are restricted to a lower speed limit, they reduce lane switching (which uses up two lanes capacity) and the need for braking behind which sends shockwaves down the lane. It also seems to work, reducing accidents (and the associated delays) by 55.7% and most drivers (60%) saying they'd like to see more of this kind of traffic management elsewhere on the road network.

The purpose then of these traffic management tools is to maintain flow and to essentially avoid "flow breakdown" by actively managing driver behaviour.

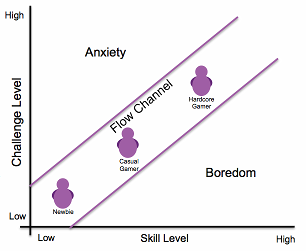

It's not just traffic management which benefits from directing peoples behaviour, games designers also utilise flow control. Based on a concept originally proposed by Hungarian psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, flow is the mental state someone is in when fully immersed in an activity. Maintaining flow within a game or keeping people playing is based on balancing a users skill level with a games challenge level. A games designer has to manage these two aspects for any game to ensure different users with different skill levels are always kept engaged.

Make it too easy and they'll get bored and move on. Make it too hard and they'll become anxious and frustrated and move on.

At a recent gaming conference called Games for Brands, speaker Mike Hawkyard from games design company 4T2 explained how they actively manage this within games they make for brands like Lego, making the game slightly easier each time a user fails to complete a level until their skill level and the games challenge level are balanced.

Flow is also something we have within loyalty programmes, even if we're not actively managing it.

Within a loyalty programme the skill aspect of flow is a little different. There may be some skill in terms of making the right choices to get the best from a programme, but this is also controlled to a great degree by ability. For example, I may have the desire (and skill) to get to Platinum tier, but if I don't have the reason (or money) to fly enough or stay enough then that skill alone won't be enough.

However, for those customers who have the ability to do more, something we term headroom, then flow becomes a big part of a loyalty programmes appeal. Making sure members have sufficient challenge is important for keeping them engaged, whether this is the rewards and their achievability, the tiers and how they are attained or achievements and how these are gained.

Loyalty programme design needs to take account of this such as using early days engagement journeys to on-board members or making sure that top performing members don't "top out" of the scheme and cease to have any meaningful challenge.

Most important though is a customers personal journey. In the same way that games designers actively manage each and every round of game play, we need to make sure we actively manage each and every customer journey using targeted and triggered communications and offers so people come back for more.

Keeping them in the zone. Keeping them engaged. Helping them flow.